Religious minorities in Iran face cultural violence

This article was first published on the website Global Voices, and is republished here with kind permission.

Over the last 45 years, the Islamic Republic of Iran has weaponised textbooks, religious debates, films and television series, city walls, and even cemeteries to impose cultural violence and institutionalise its dominance, particularly over religious minorities.

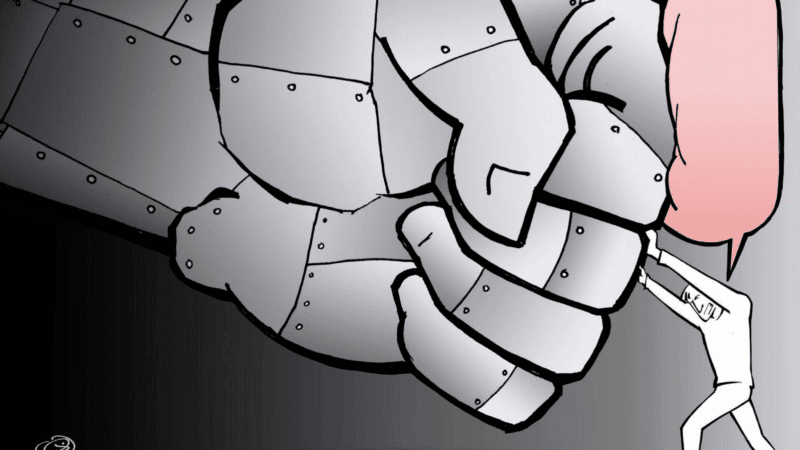

The government has employed physical, structural, and cultural violence against religious minorities. While physical violence (prison, destruction of worship places, execution, confiscation of properties), and structural or legal violence (discrimination in the labour market and education, testimony in court) are often tangible, cultural violence (art, religious debates, education) is more nuanced. But cultural violence not only facilitates direct (physical) and structural violence but also legitimises violence, making it acceptable in society.

The mention of discrimination or persecution brings to mind those officially recognised in the constitution — Jews, Zoroastrians, and Christians, with converts excluded — and the minorities who are not recognised in the constitution, including Baha’is, Christian converts, Mandaeans, and followers of the Yarsan religion. Iran goes to the extent of turning them into “ghosts” through a discriminatory policy that affects a diverse array of believers, including Sunnis, and dervishes — who are Twelver Shiites, which is the official religion of Iran.

Cultural violence transcends religious minorities, affecting broader society. Many Iranians face multiple layers of discrimination due to their complex identities. For instance, a Baloch woman experiences triple discrimination based on her gender, ethnicity, and religion, demonstrating the intersectionality of oppression.

‘Class’ of oppression

Iran’s education system oppresses religious minorities, from directly threatening children belonging to these communities, to embedding the ideology of Shiite supremacy in textbooks.

Saeed Payvandi, a sociology professor in Paris, comments on this:

During the Islamic Republic, all societal cultural institutions, especially the education system, propagate the belief that Islam is the ultimate heavenly religion with solutions for all societal problems among the young generation. This results in strong Islamic-Shiite propaganda not only in religious subjects but across various disciplines, constituting a form of direct cultural or even symbolic violence against religious minorities and those dissenting from government-style religiosity.

Many minorities, including Baha’is, Yarsanis, and Christian converts, are denied the right to learn their religious subjects in schools and are compelled to attend Islamic religious education classes.

According to Payvandi, “This educational system imposes constant humiliation and suffering on segments of the young generation, extending beyond schools to poison the soul of society.”

Besides the educational system, state-funded groups continuously target “non-recognised” religious minorities with so-called “historic” research books and sites. And the targeted groups have no right to discuss and reply against such propaganda.

Dehumanising minorities

In addition to the dominance of the Islamic perspective in education and books, religious or news sites periodically publish question-and-answer sessions with ayatollahs focusing on “religious minorities”. During these sessions, clerics are asked whether Muslims should consider religious minorities “najis” (impure), normalising the dehumanisation of these groups.

The impact of this dehumanisation is evident in various ways. Many Christian converts report that, when interrogated, their interrogators labelled them najis. The regime has, at times, established unexpected lines of demarcation, such as ordering Baha’i villagers to separate their cows from those belonging to Muslims. The authorities, after increasing such pressure on Baha’i villagers, have confiscated their property and forced them out of their ancestral land.

Surprisingly, civil rights activists in Iran have seldom protested against the labelling of minorities as najis.

Entertainment: Dominance and defamation

In addition to the constant presence of Islamic programmes and clerics promoting the state’s version of Islam, television and state-controlled film production in Iran feature numerous films that propagate Islamic values and ideology across various genres, from comedies to social or war-themed productions.

Over the four decades of rule by the mullahs alongside the Revolutionary Guard (IRGC), some films portray them in a one-dimensional and propagandistic light. The mullahs are depicted alternatively as simple mystics who earned their living through hard work and helping others, or as clergymen victimised by their own family’s corruption but fighting for justice (for example, Rooze Balva, meaning “Riot’s Day”).

Dialogue in some films easily categorises people into “Muslims” and “infidels” or “outsiders” (see Shahr-e-Mahtabi, meaning “Moonlight City”), where there is no place for religious minorities.

The Iranian Jewish community, in an open letter to the head of Iranian TV in the early 2000s, criticised and protested the broadcast of a series, “Dasiseh” (conspiracy), which “insults our religion”.

Ideology and urbanism: Feeling like a stranger in your city

Since the early days of the Islamic revolution, the regime has imposed its ideological signs and symbols on every corner of cities, conveying a clear message: the public space belongs to the state.

Joshua Hagen, dean of the College of Letters and Science at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, who wrote on Nazis and urbanism, explained to Global Voices by email:

“Sponsorship of murals, posters, banners, and other public displays serves political agendas, marginalising or excluding various social groups. In Iran, efforts to communicate regime ideology through public space act as constant reminders, pressuring individuals to conform to the regime’s wishes or, at the very least, understand the consequences of diverging from regime ideology. This dynamic, present in both democratic and non-democratic contexts, is a common feature of human behaviour and engagement with public space.”

Alongside the Islamic and revolutionary names of public places, municipalities and government foundations, citizens are surrounded by slogans and Islamic values through banners and wall paintings. Governmental institutions decorate public places, such as schools, with murals featuring verses and quotes from the prophet of Islam and Shi’a imams, praising Islamic values such as hijab.

The Islamic Republic also eliminates many signs of religious minorities from the urban landscape, even attempting to control the “afterlife” for several religious minority communities by destroying their referential and symbolic places and monuments, for example, by destroying Baha’i cemeteries, depriving Christian converts of their graveyard, or making changes to the Kharavan cemetery where many executed political prisoners were secretly buried.

Resistance and creativity

In the face of government violence and cultural aggression, minorities have demonstrated resilience. The Iranian government expelled Baha’i students and denied them education, prompting the establishment of the Baha’i Virtual University as an alternative organisation. Persian-speaking Christians faced a lack of worship spaces and educational centres, but the underground house-churches are active in the country, despite mass arrests and repression, and the converts launched a “Place2Worship” campaign. Meanwhile, the Yarsan minority employs art and music to resist de-identification policies.

Simultaneously, individuals outside the religious-minority community have actively joined the campaign for equality.

In response to grand ayatollahs denouncing pagans, communists, atheists, and Baha’is as “unclean”, Mohammad Nourizad, a political activist and journalist, invited people to visit Baha’i and atheist houses and share food with them. He even visited the house of a Baha’i prisoner and kissed the foot of a Baha’i child.

In the film “Lerd” (A Man of Integrity), Mohammad Rasoulof, the renowned Iranian director, addressed implicitly the persecution of Baha’is, including their expulsion from schools and denial of burial rights. Rasoulof faced multiple arrests, imprisonment, and the banning of his films by Iranian authorities.

Resistance to religious apartheid isn’t limited to elites; it emerges from the masses and ordinary citizens. In the 1980s, the state aimed to marginalise food shops owned by religious minorities, forcing them to announce: “This shop belongs to religious minorities,” displayed at the entrance. However, this discriminatory policy failed, and many customers became more enthusiastic about purchasing from these shops, as some mention it as a civil-rights disobedience action.

The history of combating religious apartheid intertwines with the fight against gender apartheid, exemplified by the “Women, Life, Freedom” national movement. Iranians from diverse ethnic, gender, and religious backgrounds have collectively fought for their dignity, freedom, and identity.