Religious Minorities in Iran: Persecution Meets Resistance

Fred Petrossian*–Security forces break into your house in the middle of the night. They confiscate your cell phones, photos, and religious books. They interrogate you, and maybe even have you beaten and jailed. You will be deprived of your business and education. Your crime, in the eyes of the Islamic Republic, is your religious identity—and the authorities will do all they can to break it.

Many members of religious minorities who have not surrendered to the will of the regime and its de-identification policies had this bitter experience. Some were even murdered or executed.

It seems this de-identification policy aims to publicly dehumanize religious minorities when the leading figures within the Islamic Republic including Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader, call them “impure” according to the Islamic jurisprudence.

Many members of religious minorities who have not surrendered to the will of the regime and its de-identification policies had this bitter experience. Some were even murdered or executed. It seems this de-identification policy aims to publicly dehumanize religious minorities when the leading figures within the Islamic Republic including Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader, call them “impure” according to the Islamic jurisprudence.

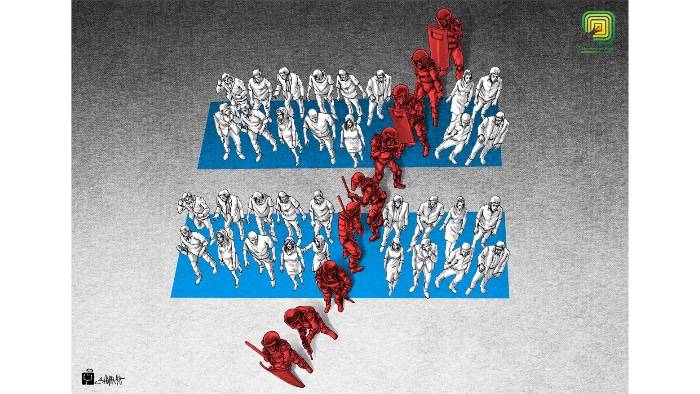

The regime is not only seeking to harass religious minorities and deprive them of equal rights like what happened to the Black population during the apartheid era in South Africa, but also seeks to destroy their identities, to dissolve them into its religious framework, and to eradicate “undesirable” minorities.

Identity Suicide

The State’s persecution of religious minorities does not only result in physical and psychological harm. Sometimes the victims are forced to commit identity suicide and accept the repressive discourse that says they are second or third-class citizens and must obey without question.

Reza Kazemzadeh, a Belgium-based psychologist and writer, says: “Here we are confronted with the manifestation of a well-known phenomenon called ‘internalization of the will of the executioner by the victim.’ The belief that the less they know of us, the less they will harass us, is a kind of public distrust not only of oppressors but also of humanity in general and of anyone who is not like us and does not share the same fate with us. That is why any plea for justice basically comes with repairing and reconstruction of social relationships. From this point of view, a plea for justice is considered a kind of dressing the wounds of society and strengthening human bonds.”

This mindset leads many people belonging to religious minority groups to accept that, in a country where their ancestors have lived for hundreds and thousands of years and sacrificed their lives to defend it, they cannot enjoy the same rights as a first-class citizen.

James Baldwin, author, and voice of the American civil rights movement, writes: “…to convince oneself that one life is worth less than other lives and that the oppressed people can live only on terms dictated to them by other people, is worse than committing a crime… It’s a sin.”

No Fear, No Shame

For decades, the Iranian regime has tried to institutionalize fear in Iran’s minorities and make them second or third-class obedient citizens. Baha’is, Yarsan, and Christian converts have been turned into ghosts and are not officially recognized. People belonging to the latter group are targeted by the regime if they emphasize their identity and do not adhere to the state religion; as a result, they face various persecutions—from educational and employment deprivation to imprisonment and execution.

State propaganda against minorities has described ordinary citizens who defended their country during the Iran-Iraq war as strange creatures with specific attributes. Christian converts are accused of “promoting Zionist Christianity”, and Baha’is are regarded as a “deviant sect”.

The regime is not only seeking to humiliate minorities as a way to force them into hiding their identity, but also trying to make them feel unsafe by raiding their homes and businesses.

Despite the regime’s efforts at repression, many members of religious minorities are not ashamed and are not deterred from emphasizing their identities. They do not succumb to the pressures when enrolling at university or in court, and by declaring their beliefs practice civil resistance against the regime.

Despite the regime’s efforts at repression, many members of religious minorities are not ashamed and are not deterred from emphasizing their identities. They do not succumb to the pressures when enrolling at university or in court, and by declaring their beliefs practice civil resistance against the regime. The cost of such resistance has in many cases been employment deprivation, imprisonment, and even execution; it should be remembered that since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, several Christian leaders and more than 200 Baha’is have been killed or executed.

For the past forty years, thousands of Iranians deprived of their basic rights have waged nonviolent civil resistance and preserved their identities, although it has sometimes cost them their lives. This civil resistance has creatively taken place individually or in groups.

From Home Worship to Virtual University

The repression is not limited to attacking members of religious minorities. In line with anti-minority policies of the regime, over the past four decades many minority centers and institutions—and even cemeteries in the case of the Baha’is—have been destroyed. It seems the Islamic Republic is trying to remove all religious minorities’ existence from history.

Many Persian-speaking churches and Christian community centers, including hospitals, have been closed and confiscated. Recently, an Anglican Bishop’s confiscated house was turned into “a house of mourning for Hussein”, the murdered grandson of Muhammad, and the grave of an executed priest convicted of apostasy was destroyed.

The Gonabadi Dervishes are Shia Muslims of a Sufi order and have been under a lot of pressure from the government about exercising their beliefs since 1979. Gonabadi Dervishes’ houses of worship have also been destroyed by the authorities. All of the recognized religious minorities (Jews, Zoroastrians, and Christians, meaning Armenians and Assyrians), Sunnis, and even Shiite Muslims have not been immune to the regime’s structural discrimination and violence.

Places of worship are not only for the practice of prayer and rituals but also for developing the social identity of the people belonging to a religious minority. Many religious minorities have come up with an alternative to the typical places of worship, turning their homes into a substitute.

House churches are growing in different parts of Iran, from Rasht to Bushehr, from Yaftabad in Tehran to Malayer, despite raids by the security forces, confiscation of Bibles and crosses, and arrest of the Christian converts.

The population of a few hundred Christian converts before the Islamic Revolution has now grown to hundreds of thousands.

In addition to marginalizing religious minorities, the authorities have also sought to deprive them of access to university education, whereas for decades the regime loyalists have been provided with financial aid such as grants and scholarships.

It seems that capital punishment, imprisonment and other forms of discrimination have not been enough, so the regime is also seeking to block minorities from entering universities.

In reaction to this discrimination, the Baha’is implemented a creative initiative, and established their own “Free University”. This Virtual University is run by 295 academics and staff and offers more than 922 courses. The Baha’i students are able to study for 14 bachelor’s and three master’s degrees in natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities and arts.

The Baha’is have also collaborated to help their fellow believers whose businesses have been confiscated by the regime. They have also set up an organization to care for the Baha’i seniors who lost their pensions because of their religion.

Nonviolent Civil Resistance

Religious minorities, in efforts to preserve their identity, have taken up peaceful activities, beyond holding house meetings or establishing alternative organizations such as virtual universities. They also have occasionally used other nonviolent methods to make the public aware of the persecution they face every day and to put pressure on the regime.

Religious minorities, in efforts to preserve their identity, have taken up peaceful ideological activities, such as holding house meetings or establishing alternative organizations such as virtual universities. They also have occasionally used various nonviolent methods to make the public aware of the persecution they face every day and to put pressure on the regime.

Examples include Demonstration of Yarsan followers in protest against the insults in Eslamabad-e Gharb; several open letters from the Advisory Forum of Yarsan Civil Activists to the regime leaders calling on them to stop discrimination; a letter by a Christian convert to the Minister of Intelligence about deprivation of the right to have a church and creating the Instagram campaign “The church is the right of Christians”; hunger strikes of imprisoned Christian converts including Yousef Nadarkhani, who protested against deprivation of his children of the right to education; hunger strikes of imprisoned Gonabadi Dervishe women following organized violence that was done by the prison’s guards at the Qarchak Prison; the gathering of thousands of Gonabadi Dervishes in front of Parliament to protest the damage to their house of worship by the authorities in Isfahan.

These are all forms of protest against the religious apartheid in Iran. Religious minorities defend their basic rights and say: “We exist.”

Women in these religious minority communities have played a vital role in civil resistance and identity preservation through different ways, ranging from holding worship meetings and training courses to hunger strikes in prison.

Women in these religious minority communities have played a vital role in civil resistance and identity preservation through different ways, ranging from holding worship meetings and training courses to hunger strikes in prison.

Over the past four decades, many of them have paid a high price for resistance, ranging from imprisonment and torture to execution. We can mention 17-year-old Mona Mahmoudnizhad, who was accused of teaching Baha’i faith to children and hanged along with nine other Baha’i women in Shiraz. In a recently-published book “White Torture,” five female prisoners of conscience including two dervishes, two Baha’is, and a Christian convert, have told their stories of harassment in prison and resistance to interrogation and mental breakdown.

These women, like many others, said to the regime: “We exist, we preserve our identity, and submission is not an option.”

- Fred Petrossian is Editor in chief of MvoicesIran. Fred is advocating for freedom of belief in Iran. He was Iran editor in Global Voices and Online Editor in Chief of Radio Free Europe’s Persian service. He is co-founder of the award-winning March 18 Movement to raise awareness about bloggers in the world.